Roger LeBaron Hooke passed away on 10 March 2021, a few days after sustaining severe head injuries in an ice-skating fall. He was 82 years old. As his widow put it to me, the ice finally got him.

Roger’s scientific contributions covered a wide range of topics, but those who took his courses recognized that his main motivation was to get at physical processes that make the landscape. Teaching geomorphology using the Socratic method, which could be terrifying to new graduate students, a favorite question was “where’s the physics?” Very few things generate a force to move sediment and water and ice and soil, and how do you make the connection from these few things to what you see in the landscape?

Roger grew up in Montclair, New Jersey, as the son of an electrical engineer. However, he had deep New England roots — a descendent of Myles Standish from the Mayflower, with a family home in Castine, Maine, from the late 18th century. After graduating Harvard College in 1961 with a degree in Engineering and Applied Physics, he entered the PhD program in Geology at CalTech, where he worked under the supervision of Robert P. Sharp. The shift towards geology was influenced by a geology major at Smith College, Ann Peck, with whom he would share a 60 year marriage.

Roger’s scientific career is most simply described as broad, encompassing several areas of geomorphology, several areas of glaciology, and glacial geology. His techniques included field work, laboratory experiments, instrument design, and quantitative analysis that included mathematical theory, empirical studies, and numerical modeling. His dissertation work was in desert geomorphology, on the growth and form of alluvial fans. He elucidated the processes that control the slope of alluvial fans in steady state. Two papers resulting from this dissertation have been collectively cited more than 400 times. His interest in desert geomorphology continued as one thread of his career for decades, with occasional field trips to the Mojave. A 1992 paper on desert varnish won the Earth Surface Process & Landforms award for best paper of the year in that journal.

After receiving his PhD in 1965, Roger took a professorship at the University of Minnesota, which he would hold for 35 years. Early on at Minnesota, he began to work on fluvial geomorphology. While much of his scientific legacy is based on field projects, his dissertation also involved laboratory measurements of sediment flow on a small scale, and work with flumes and stream models became more important in his early academic career at Minnesota. A significant part of this work explored how sediment moves in response to shear stress fields in meander bends, with the primary result demonstrating that sediment mostly moves through the inside part of the bend, where velocity is relatively low but that the forces exerted are relatively high. This result surprised almost everyone in the field, and subsequently led to other important research by others on meandering rivers. Roger also published a short but highly influential paper justifying the use of small-scale laboratory models of geomorphic systems that continues to motivate experimentalists today. Roger provided important insights into the framing of watershed sediment budgets, parsing out supply contributions at the catchment scale relative to processes of sediment delivery with guidance on analytical expressions to estimate watershed sediment yield.

Roger with a Swedish technician at the flume in

Uppsala, Sweden, 1971.

The glaciological component of his research began in the 1960s, no doubt inspired by his PhD advisor, Bob Sharp, who like Roger mixed glaciological and geomorphological interests. Roger’s first significant field work on a glacier was not his own research; rather he was a field assistant on the famous Clair Patterson expedition to Greenland in 1964, helping obtain ice samples to prove that atmospheric lead levels had risen dramatically after the introduction of tetraethyl lead in gasoline. It was extremely important to not have post-nasal drip on the samples, because humans at that time had far higher lead levels in their bodies than would be in the old ice.

In the late 1960s, Roger began working with a Canadian group on the South Dome of Barnes Ice Cap, Baffin Island, making mass balance measurements and taking ice samples for crystal fabric studies. In 1970, working with Gerry Holdsworth, he started a different field campaign there that would continue for 14 years. They established a strain net of 43 stakes along a 10 km flow line. Initial studies were of surface velocities, mass balance, and crystal fabrics. Over the course of the project, boreholes were added to emplace square aluminum tubing for inclinometry and to assess the internal temperature field of the ice cap. An early assistant on Baffin was Bruce Koci, getting his introduction to ice drilling from Roger. Bruce would go on to become, as Richard Alley once said, “one of the unsung heroes of ice-core science.” PhD student Robert Baker was brought in as field assistant and to work on the crystal fabric studies, and Minnesota colleague Peter Hudleston, a structural geologist, helped understand the flow. Making use of the wealth of intensive data for a small flowplane, Roger enlisted help from finite-element modelers such as Charlie Raymond and started a program of both velocity and temperature modeling for the flowplane.

The Baffin Island projects yielded results in several areas of glaciology. The long mass balance record, including not just net mass balances but elevation profiles of mass balance, led to the understanding that there were a complicated set of feedbacks with temperature in polar ice caps, such that an increasing climatic temperature would increase surface slope, leading to faster flow to the ablation area, but subsequently that flow would decrease surface slope. Roger also deduced that a complex stratigraphy near the margin of the Barnes Ice Cap flowplane resulted from the ice overriding its own frozen toe in an advancing phase. It was a cautionary tale about being simplistic about glacier flow. He and his colleagues determined that the bottom layer of Barnes Ice Cap was a remnant of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, and that it had significantly lower density and viscosity than the Holocene ice, primarily because of a higher air-bubble content, leading to the counterintuitive result that the ice cap might have slowed and thickened as the softer Pleistocene ice layer thinned. Based on both literature review and crystal-orientation studies, Roger significantly improved our understanding of the temperature-dependent coefficient in Glen’s power law for flow — an important contribution to the modeling effort.

The Barnes Ice Cap field seasons were logistically difficult. While field studies had been carried out on Barnes for decades, there was no permanent infrastructure or nearby airstrip. There was a strip that a courageous bush pilot might land on about 20 km away, but the nearest maintained airstrip was at Clyde, 120 km and a two-day snowmobile ride away. Flights in and out were regularly delayed in the Arctic weather, and these all had to be arranged by Roger, not coordinated with a well-prepared NSF logistics program. Communication with the outside world was via shortwave radio, for which Roger did not have a highly reliable antenna, and all the food, fuel, and new equipment for each season had to be thought through in advance and transported. Any problems during the season had to be fixed with what was available, so having one of the field assistants be a snowmobile mechanic was useful. Roger liked to tell the story of doing a makeshift repair using a nail heated by a camp stove as a soldering iron. Although the slopes of the ice on Barnes Ice Cap are not high compared to alpine glaciers, the surface could be dangerous to travel on. Roger had stories of long detours around surface meltwater streams and crawling on his belly across a snow bridge he didn’t trust in order to spread out his weight.

Roger’s colleagues on Baffin Island considered him to be a virtuoso of camp cooking. He specialized in breakfasts, alternating sourdough pancakes with various porridges. His field assistants guessed that the breakfast specialty was to make sure that none of the crew were sleeping in. While others typically prepared dinner so that Roger could keep working, he weekly came up with a dessert treat that everyone looked forward to: shortcakes or coffee cakes using dehydrated berries or pineapple chunks.

Roger’s second major glaciological campaign overlapped with the waning years of the Barnes Ice Cap project, but it was similarly long-lived and similarly started simple and grew to become comprehensive. Roger developed connections in Sweden during a sabbatical doing flume experiments in Uppsala in 1972. His second sabbatical was at the University of Stockholm in 1980, which led to a friendship with Valter Schytt, the founder of Tarfala Research Station and the initiator of the now 75 year Storglaciären mass balance record. For the next 15 years, most of Roger’s fieldwork would be associated with Storglaciären (and Rabot Glacier on the other side of the mountain).

Valter Schytt had chosen Storglaciären as a place to establish a research and teaching facility for several reasons, one of which was that it was relatively safe to get around on. Most of the accumulation zone required roped-up parties of at least three to traverse (one particular crevasse had a name, “the bus garage,” and we avoided that area), but much of the ablation zone did not require ice-climbing or safety equipment to get around on, once a person was oriented to the crevasse zones and the area that was dotted with moulins. Tarfala was 25 km by trail from the end of the road, but helicopter support was close because Storglaciären flanks Kebnekaise — a popular tourist destination as the highest point in Sweden. Also, Valter had established Tarfala Station just after WWII, and over time it had grown to include a lab and workshop for building and calibrating instruments, a mess hall and kitchen hut, a shower and sauna hut, and warm, dry sleeping huts, including electric power and a radio-telephone system to communicate with the outside world. It was basic, but to someone whose experience leading a glacier fieldwork campaign was on Baffin Island, it seemed luxurious.

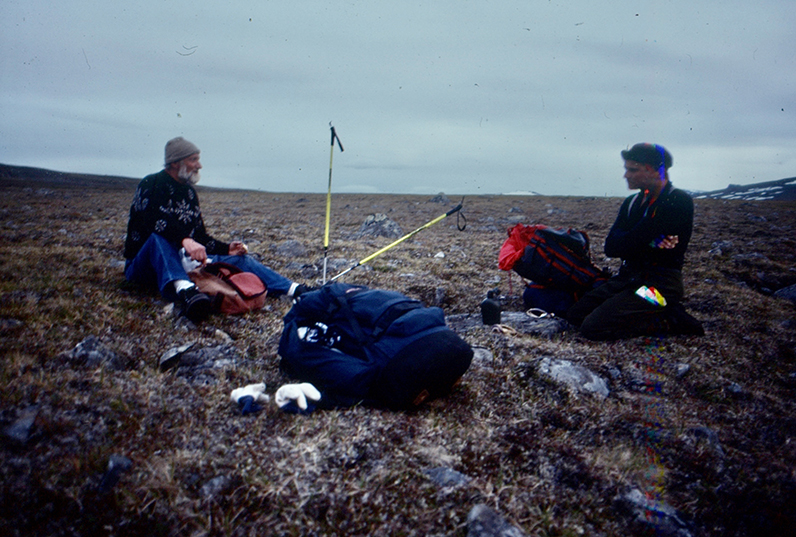

Santa and three elves? Roger with three field assistants from University of

Wisconsin – River Falls, Baffin Island,

1979. Photo by Bob Baker.

The studies carried out by Roger and his students at Tarfala started with glacier hydrology, including boreholes for salt-tracing and dye tracing experiments, hydrologic measurements in the outflow streams, sending a video camera down a borehole to analyze the intersection between conduits and the hole, and surface speed and strain-rate measurements, first as repeated theodolite surveys and later as short-time-resolution surface speed and strain rate with automated distance meters. A few borehole inclinometer measurements were also done. Finding that the internal conduit system tends to break down over winter and rebuild when there is a lot of meltwater and rainwater in summer was a significant element of the results, and also that there was no single relationship between internal water levels and glacier speed because it developed through the season.

In the late 1980s, the glaciology world became seriously interested in the effects of till layers at the bottom of glaciers, especially as they related to West Antarctic ice streams. The paradigm shift from Weertman’s “tombstone” model to a till layer required understanding till deformation. Roger, in close collaboration with PhD student and later post-doc Neal Iverson, and using some ideas from Garry Clarke’s group at UBC, began designing experiments and instruments to work on till deformation on Storglaciären, where we already knew a till layer existed from previous drilling for the hydrology experiments. The last few years of the Sweden work were focused on till-deformation studies, and they led to several papers that are still regularly cited after 25 years. The final results of these experiments did not indicate that till behaved viscously or deformed consistently at depth. Rather, till behaved as a plastic material in which shear resistance increased with effective pressure, and slip occurred at the bed surface when effective pressure was sufficiently low.

Of Roger’s 12 PhD graduates, 9 worked with him at Tarfala, and 6 received their PhD based primarily on work done there. The research group would gather for coffee in the library after dinner, go over the day’s results, discuss preliminary graphs if we were getting data, and plan the next day. It was a dynamic project, where the success depended on a lot of people giving input into how our work would change the next day, in part because most of the instruments were new designs and we were refining our understanding of how to install them and interpret the data. Nobody who was there would disagree that Roger was the leader, bringing the best out of all of us to generate some important results.

With Brian Hanson overlooking Rabot Glacier, 1988.

On Saturday night, the work at Tarfala would slow down. The cooks would break out some bottles from a well-hidden stash of Chilean red wine, and Roger would take an evening off from working on the project and reminisce a little. The cooks at Tarfala had Sundays off and various volunteers filled in. Roger’s Sunday morning tradition was to make sourdough pancakes for everyone. Tarfala station was acquiring real maple syrup for these breakfasts, and the pancakes were excellent. Some Swedes were a little befuddled because pancakes are not usually a breakfast food in Sweden. The tradition of making sourdough pancakes on Sunday morning, using Roger’s recipe, was carried on for many years after Roger’s projects there were over.

Roger’s last field season in Sweden was 1995, and while papers about Storglaciären continued to come out for another few years, his research had moved in several other directions. He, along with his PhD graduate Paul Cutler, proposed a significant field and modeling campaign for a tidewater calving glacier in Alaska. The proposed field program was ambitious but had several technological long-shots. It was not funded and only a modeling portion of that project was completed. A close approximation of what he was proposing has been carried out in the last few years using drones, radio-controlled kayaks, and digital time-lapse cameras. Everything that was proposed was a good idea, but technologically two decades too soon. Roger never led another major “leave all summer and go to the Arctic” field campaign, but he continued to do field work for the rest of his life.

A lasting element of his post-Sweden work was the completion of Principles of Glacier Mechanics, with the first edition in 1998. Those of us who took the course on which it was based recognize that it reflected his interests, and that it was also bringing difficult concepts to a level of explanation that was needed by his graduate students. The third edition was published in early 2020 — a project he was keeping current into his 80s.

Taking a break with field assistant Hjalmar Loudon in the middle of the night during the walk out of Tarfala, 1992.

Roger’s influence in geomorphology extended into natural resources and watershed management disciplines through his work to identify and quantify human activities as geomorphic agents in varied landscape settings and globally. His first published paper on this was in 1994, but already in the 1970s he was incorporating human-impact ideas into his geomorphology field trips, trying to get students to recognize that some of the landforms they were seeing were a result of human interference and not natural process. One of his hints was to refer to something as the “Caterpillar Formation,” where he meant that we should think of earth-moving equipment, not larval butterflies. A 2012 review paper he co-authored in GSA Today has received more than 440 citations. It closes with a strong environmental plea for us all to damage the landscape less in the course of extracting the resources we need. A chapter Roger contributed to a book edited by José Francisco Martin Duque, one his co-authors of the 2012 paper, has yet to appear in print, so it is possible that Roger’s final contribution to science will be on human impacts.

In the 1980s, Roger and Ann had acquired land on the shore of Deer Isle, Maine. He built a small house over a garage there while developing a plan for a permanent retirement house. The small house became his guest house when by 1992, the “big house” was built. He spent nearly every August there after his field seasons were over, but in 2000 he retired from the University of Minnesota and moved to Deer Isle permanently.

Roger and Ann in their two-seat kayak, Deer Isle 1992.

“Retirement” in this case just meant that he stopped taking a salary or a teaching obligation. Well before retirement, Roger developed an informal Adjunct Professor position at the University of Maine, and on retirement this turned into a Research Professor position. For the rest of his career he used the Maine byline. Roger was an ever-present member of the School of Earth and Climate Sciences at Maine. Even though he lived on Deer Isle, he spent several days a week during the academic year staying in Orono where he owned a townhouse and had an office in the School’s building. He made a point of attending monthly faculty meetings and weekly research seminars in the School. Roger taught at least one graduate course each year in the School, without compensation, alternating Geomorphology and Glaciology. His courses were known in graduate-student lore to be the most challenging in the School. The graduate students had many colorful stories relating to the quantitative problem sets that he would assign. But Roger always received very positive student assessments of these courses, and the graduate students always spoke highly of him as a person and teacher — he was generous with his time and supportive of both students and faculty who engaged with him on a variety of geomorphology and glaciology topics. Roger also sat on numerous Masters and Doctoral thesis committees over his years in SECS, and the School helped to support some of Roger’s local research activities in return for his generous contributions to teaching and advising.

In Maine, Roger’s research reflected his location and included the glacial geology of Maine and coastal geomorphology. Early in his time at Minnesota, he had established long-term research projects where he knew that publishable results might take more than a decade. In Minnesota these included meticulous measurements of soil creep that were maintained over several decades. In Maine, he started similar long-term measurement projects of estuary stream widening, beach cliff erosion, and beach profile changes. At Minnesota and Maine, Roger used his teaching to keep these long-term measurements going. Everyone who took his geomorphology course at Minnesota helped with continuing the Rice Creek meander bend measurements and the soil creep measurements, and many of his Maine projects were executed through short courses with the Eagle Hill Research Institute. These long-term measurement series did not all lead to publications, but they were all based on serious scientific questions, and Roger used them as a combination of a teaching tool and a potential paper if the results proved significant.

In recent years, Roger focused attention on the development of landforms in the Penobscot River watershed and coastal areas of Maine, unraveling explanations for modern landscape conditions produced from deglaciation and related sediment transport dynamics. Related field trips he led were considered by the fortunate participants to be top notch in terms of pedagogy, technical explanations for complicated earth surface processes, scientific curiosity, and long-lasting memories of a meaningful, thought-provoking day in the field.

Warming a foot on the water-heater component of the hot-water drill, Storglaciären 1995.

Roger collaborated widely. The 120 publications on his CV show more than 100 unique co-authors In many cases, Roger sought these out from an awareness of his strengths and limitations. Similarly, with his PhD students, he was seldom seeking to clone himself, but was expanding the range of his work by finding students who could design and build laboratory and field equipment, establish microclimate networks, or do numerical modeling. He also improved the discipline through his two decades combined serving as an editorial board member or scientific editor of Earth Surface Processes and Landforms and the Journal of Glaciology, and as a regular reviewer of many manuscripts outside his role as an editor and as a reviewer of many grant proposals. This work included generous and meticulous efforts to improve the presentations of authors for whom English was a second language.

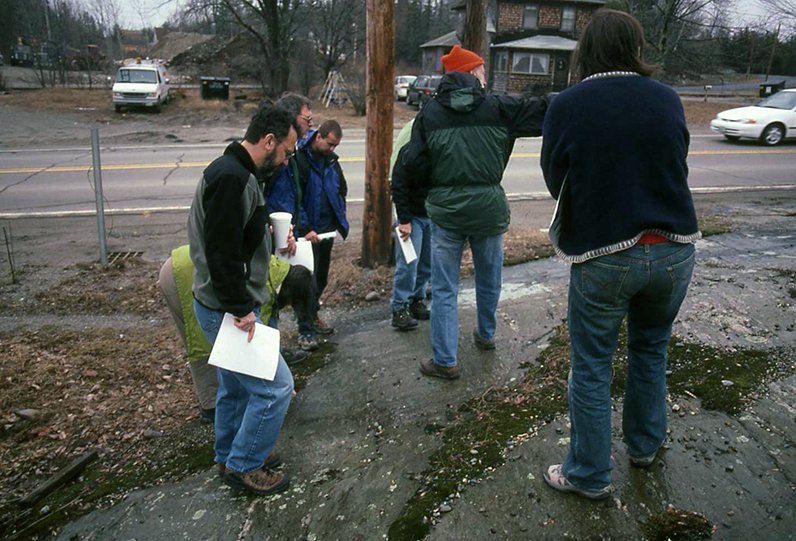

Explaining the Agassiz striations in Ellsworth, Maine, on a field trip after Midwest Glaciology

Meeting, 2003. (These striations are the first evidence of glaciation that Louis Agassiz saw in North America, and this is nationally registered historic place.)

A variety of short memorials have been circulated on email lists since we heard of Roger’s passing. A tribute sent by several former students (who also helped with this obituary) to the Gilbert Society included “Roger’s approach to science was characterized by a remarkable passion for intellectual rigor and an unwavering pursuit of excellence. His grounding in the scientific principles essential for quantification of earth system processes was steadfast through his entire career of teaching and publications.” Richard Alley, who summarized Roger’s glaciological contributions at a “retirement” session at AGU two decades ago, gave this final tribute: “Roger had an exceptional ability to find simple physical understanding in complex data. Working with outstanding students and collaborators, Roger blazed research paths in numerous important directions, including iceberg calving, glacier hydrology, basal lubrication, and the flow law of ice. The breadth of Roger’s contributions allowed him to bridge subdisciplines, helping unify the field.”

Roger and Ann led an active life of travel and adventure. In the last months before the world closed up for the pandemic, they visited New Zealand and California. Earlier Christmas letters told of visiting places ranging from the Himalayas to the Amazon to kayaking in the Arctic. They practiced their love of the outdoors at home as well, helping with trail maintenance, island cleanups, and general preservation of Deer Isle and close-by islands, working with the Island Heritage Trust.

Preparing to boil lobsters by the shore, Deer Isle 2013.

At Minnesota and Maine, Roger and Ann were generous hosts of scientific visitors and old friends. If a distant colleague or a scientific visitor came to the University of Minnesota, their house was likely to become the site of a soiree. The first Midwest Glaciology Meeting in 1992 landed there one evening. Field trips in Maine would sometimes end at Deer Isle for a dinner of Ann’s lasagna or chili. If you found your way to them at Deer Isle, the guest house above the garage became one of your favorite places, enhanced because there might be an evening of lobster boiled on a campfire near the shore. There would also be the oft-mentioned sourdough pancakes for breakfast, but now with fresh Maine blueberries.

The day I learned that Roger had died, I was working on answering a question he had sent me about calculating changes in ELA caused by small perturbations in climatic elements — he never stopped working. Roger leaves behind a legacy that includes a wide-ranging set of published results that have improved fundamental understanding across several fields. He also leaves behind a host of collaborators, students, and friends, who will cherish the memory of his impact on our lives and careers.

Brian Hanson with contributions from former students Bob Baker, Jim Pizzuto, Neal Iverson, and Peter Jansson; from his Minnesota collaborator Peter Hudleston; from his Maine colleagues Alice Kelley, Sean Smith, and Scott Johnson; and most importantly his widow Ann.

This obituary will also appear in our newsletter ICE in due course. Roger’s obituary was published in our newsletter ICE Number 185 1st issue 2021, pp29-34